James Larkby-Lahet

Systems software can often be viewed as consuming a set of interfaces and presenting a higher level interface. A potential consumer of the higher level interface is often implicitly interested in what is lost in the translation.

Interface Fidelity

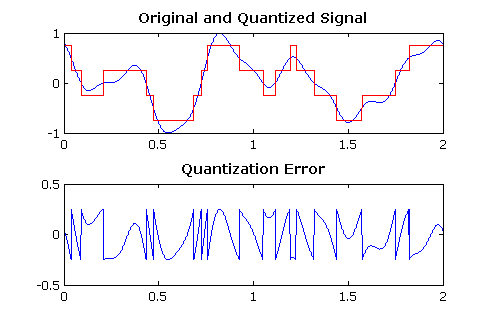

When people speak of digitization, of media, the humanities, the world, it is usually with an implicit nod to fears regarding the fidelity of the digital artifact. The process of producing such artifacts is quantization.

Regardless of encoding method, given enough bits (upping bits per sample or sample rate) we can arbitrarily bound the error. This is the marvelous hermeneutic of the digital: it maintains that given enough bits, nothing lies outside itself… the dream is real.

Writing a library, Operating System, etc. that offers an interface can present comparable fidelity issues, but without such a trivial remedy. We are taking a computational digital artifact (rather than just media), and incorporating it into a larger artifact. There is the source interface (hardware in the case of an OS, a drawing primitive library like Cairo for a window toolkit like GTK+) and the ‘destination’ interface: the interface that the software presents to yet higher levels of software.

There is no inherent reason to expect that the two levels of interface will present the same level of expressive power, in fact we often write libraries specifically to constrain expression, often under the banners of simplicity and/or correctness. However low-level privileged code (which is forced upon all users) has a special need to retain as much flexibility as possible, since its interface is mandated. In addition, the tension between expressiveness and ease of use is the main source of our continual production and rewriting of libraries providing these interfaces.

To discuss expressivity I think the best formal grounding is information theory. We can think of a higher-level, destination interface as a compression of a low-level source interface. While matters are complicated by state that may be hidden in the interface, the intuition is that if every source symbol has a corresponding destination symbol, the compression is lossless, and the interfaces are of equal expressiveness. A necessary but not sufficient shortcut for these kinds of examinations is: if the number of states (symbols) for the low-level interface is greater than the high-level one, they cannot have the same expressive power.

In striving to fully realize the flexibility of the exokernel design, the XOmB kernel attempts to provide lossless interfaces to hardware. It does so with two important design features. The first is statelessness; this simplifies matters because the only state is that which resides in the source interface. The second is direct exposure of the hardware to the greatest extent possible. The combination of the two make a comparison of expressiveness trivial, because the interfaces are the same. This is in stark contrast to POSIX-compliant systems where the interfaces are so complex, stateful and dissimilar to hardware that it is difficult to know where to start in trying to make similar evaluations.

In short, XOmB’s design is not a result of obtuseness or devotion to an ideal, so much as laziness when it comes to trying to make formal claims. The expressive equivalence of XOmB is so obvious I debated whether this post was worth writing at all. However, I think we need to think more about how we make claims about interfaces, particularly in light of wilkie’s discussion of interface design and our joint frustration with the way we currently mis-evaluate software designs.

<3